The Lachlan valley has an area of 90,000 square kilometres, extending from the Great Dividing Range to the Great Cumbung Swamp on the Riverine plains. Nearly 1300 kilometres of the 1400-kilometre-long river is regulated by water storages, of which Wyangala Dam is the largest at 1220 gigalitres.

The Lachlan catchment recovered rapidly from drought conditions in 2020–21 with La Niña conditions bringing rainfall in August–September 2020. Two translucent flow events (environmental water under water sharing plan rules) occurred in August–September and October–November 2020, totalling 173,000 megalitres. Consequently, water for the environment was managed primarily to supplement translucent flows and extend the duration, depth and connectivity of floodplain inundation in the lower Lachlan.

Water managers prepared for the 2020–21 year with a forecast of nil to low water allocation. This corresponded with an expected very dry to dry resource availability scenario, as identified in the Lachlan catchment: Annual environmental watering priorities 2020–21. There was zero allocation for general security in 2019–20. The aim under these conditions was to maintain strategic drought refuges to avoid irretrievable loss of species and habitat.

Minimal inflows occurred in 2019 – close to the record minimum. However, substantial inflows in August increased Wyangala Dam capacity from 16% in July 2020 to 70% in April 2021 and water allocations were increased accordingly. The first general security allocation in 3 years occurred in September, and again in November 2020 and April 2021. This meant the environmental water allowance (20,000 megalitres) also became available in April 2021.

Supporting key refuge sites

Maintaining key drought refuges, such as Booberoi Creek and Great Cumbung Swamp, was the focus in the Lachlan early in 2020–21. Although drought intervention was not required, water for the environment was delivered from May to July to increase unseasonably low base flows. This helped maintain permanent refuge habitat for threatened species such as southern bell frog in Cumbung, and macrophytes and native fish in Booberoi Creek.

Unprecedented collaboration between the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment, WaterNSW, local landholders, local fish experts, Department of Primary Industries – Fisheries and the local Aboriginal community to remove constraints and increase channel capacity of the Booberoi Creek delivery system was successful, with subsequent translucent and licensed environmental water delivery exceeding expected flow efficiencies and ecological outcomes.

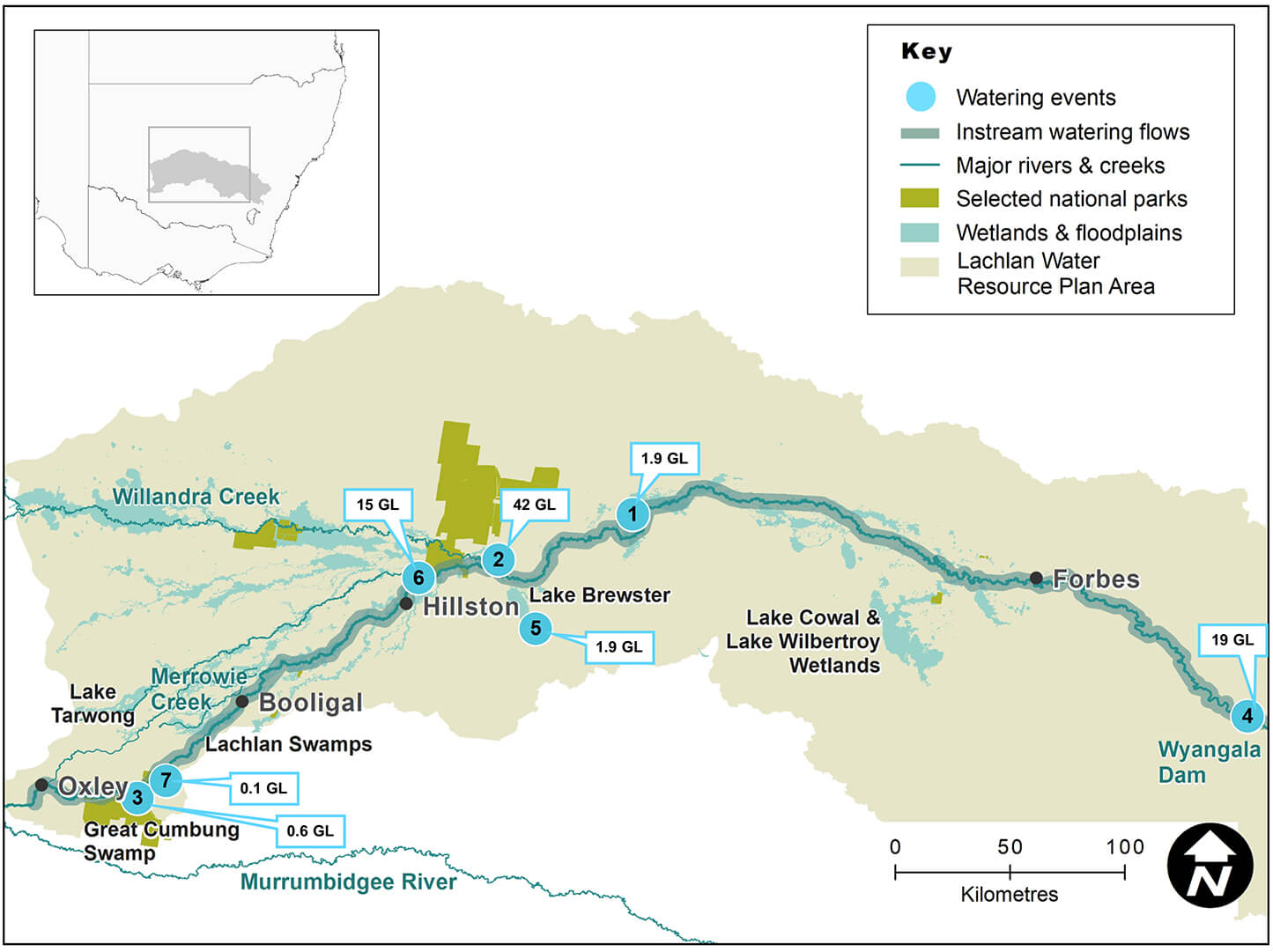

Lachlan catchment area map

Watering aims

The delivery of NSW and Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder water for the environment in the Lachlan catchment during 2020–21 quickly moved from maintaining priority refuge pools and avoiding loss of species and habitats to delivering substantial parcels of water to maintain connectivity between the Lachlan River and its floodplain habitats and ecosystems.

The watering aims identified in the Lachlan catchment: Annual environmental watering priorities 2020–21 under very dry to dry conditions were met and expanded in line with wetter catchment conditions. This included supporting colonial waterbird breeding and providing food and shelter for newly fledged juveniles. Flows were maintained for several weeks after translucent pulses in summer to avoid sudden drops in river heights and inundate more in-channel habitat for native fish post-spawning including Murray cod and golden perch. This was repeated over winter in the lower Lachlan.

Hundreds of kilometres of fringing channel habitat and lignum shrublands were watered after stock and domestic replenishment flows in Muggabah, Merrimajeel and Merrowie creeks. This included follow-up flows for the Booligal Wetlands complex, such as Murrumbidgil Swamp, which last received drought management flows in 2019–20, to build further resilience, and Lower Gum Swamp, which was last watered in the 2016 floods.

Water delivery

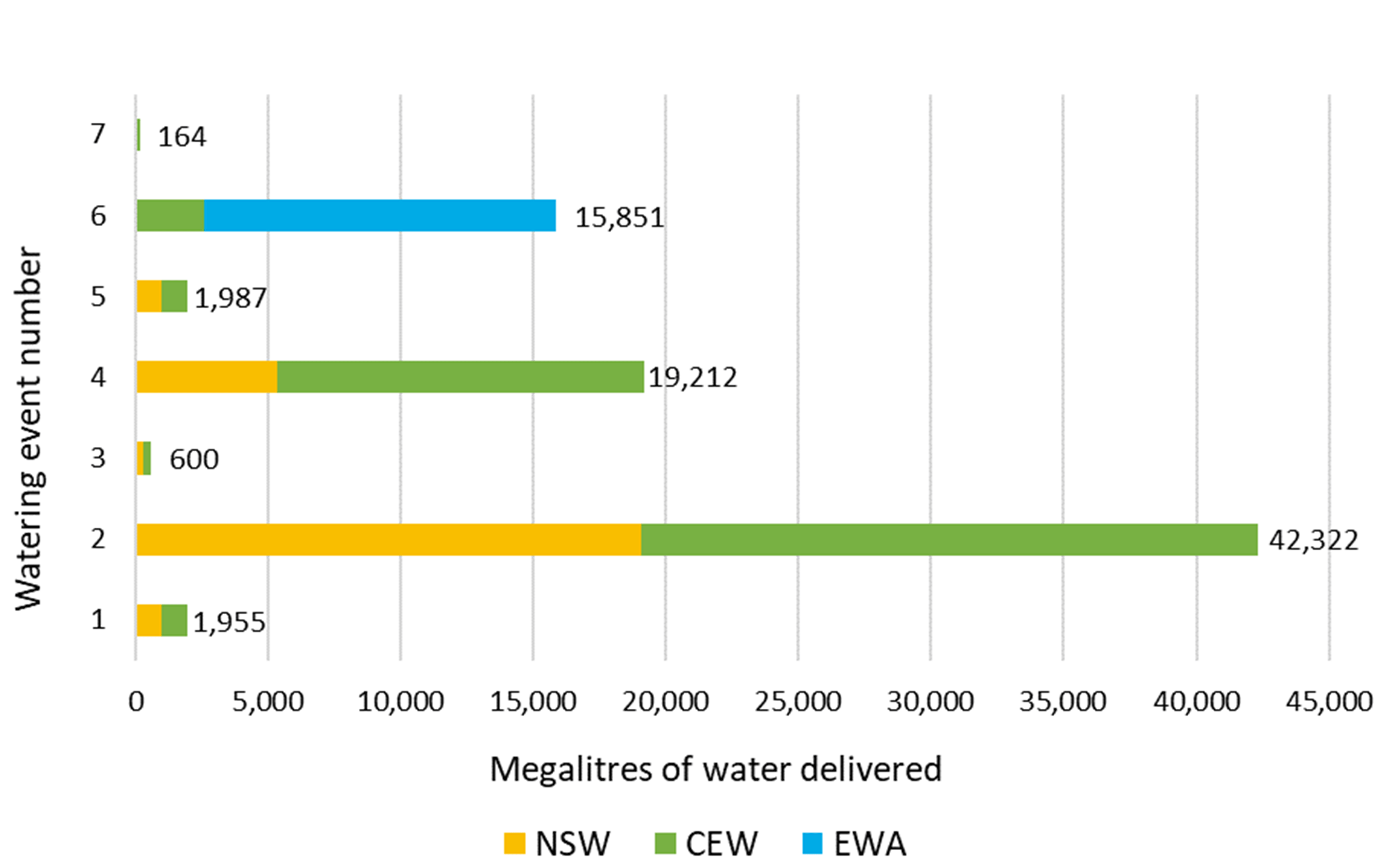

This bar chart and table provide a summary of 82,091 megalitres of water for the environment use in the Lachlan catchment during the 2020–21 watering year. Volumes are indicative only. Watering event numbers in the bar chart and table relate to location numbers marked on the map.

Water delivery to the Lachlan catchment in 2020-21

| Watering event number | Location | Outcomes | Start date | Finish date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Booberoi Creek | Native fish Connectivity | 17 Sep 2020 | 26 Oct 2020 |

| 2 | September post-translucent flow | Native fish Vegetation Connectivity Waterbirds | 17 Sep 2020 | 02 Nov 2020 |

| 3 | Fletchers Lake | Waterbirds | 02 Nov 2020 | 19 Nov 2020 |

| 4 | November post-translucent flow | Native fish Vegetation Connectivity Waterbirds | 06 Nov 2020 | 19 Dec 2020 |

| 5 | Brewster outflow wetlands | Waterbirds Vegetation | 11 Jan 2021 | 03 Apr 2021 |

| 6 | Autumn multi-event | Native fish Vegetation | 07 May 2021 | 30 Jun 2021 |

| 7 | Noonamah blackbox wetland | Waterbirds Vegetation | 10 Jun 2020 | 22 Jun 2021 |

Notes: NSW = NSW licensed environmental water; CEW = Commonwealth licensed environmental water; EWA = Environmental water allowance accrued under the Water Sharing Plan for the Lachlan Regulated River Water Source 2016.

Outcomes

Water for the environment focused on delivering water to large floodplain wetland complexes in the lower Lachlan, including the Booligal Wetlands, Lachlan Swamps, Great Cumbung Swamp, and Lake Brewster. This water:

- provided months of additional connectivity to thousands of hectares in these nationally significant and unique wetlands

- supported wetland habitats and food sources for wildlife

- slowed and smoothed the rate of recession of the Lachlan River height from 2 translucent flows

- improved water quality of the Lachlan River by mixing storage releases with higher carbon loads returning from floodplain

- maintained small darter, cormorant, egret, spoonbill and pelican rookeries in Moon Moon Swamp, Lachlan Swamps and Lake Brewster outflow wetlands

- maintained and supported pelican breeding at Lake Brewster, the only known colony site in Lachlan that regularly contributes juveniles to the pelican population

- inundated extensive areas of river red gum and black box woodland swamps, lignum shrublands, open lakes and tall emergent marshes in Great Cumbung

- wet core areas of reed bed, which had not flooded for more than 4 years, for extended periods, resulting in new growth and reproduction

- triggered southern bell frog calling in late spring at multiple sites in the Great Cumbung region, prompting additional flows to be delivered to provide permanent refuge habitats over autumn and winter

- provided for additional end of system flows in Muggabah Creek and for the first time delivered water for the environment into Lower Gum Swamp in the Booligal Wetlands

- supported 56 waterbird species and total waterbird abundance, the largest amount recorded in our past 5 annual spring on-ground surveys.

Case study: Flows bring life to Lachlan

Ecological outcomes from 173,000 megalitres of translucent flows in the Lachlan catchment between August and December 2020 were enhanced by over 61,000 megalitres of NSW and Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder (CEWH)-licensed water.

By early November 2020, inundation mapping and on-ground monitoring confirmed environmental flows had brought a flush of activity and new life to over 27,500 hectares of the lower Lachlan channel and floodplain habitats. In some areas this was the first time flows had arrived since the 2016 floods. This included 7 nationally important wetlands, including Lake Merrimajeel, Murrumbidgil Swamp, Booligal Wetlands, Lachlan Swamp and the Great Cumbung Swamp.

The extensive lower Lachlan River wetlands rely on river flows from the upper Lachlan. Upstream regulation means these flood-dependent ecosystems receive water less frequently, for shorter durations and at different times of the year compared to pre-regulation days. The use of licensed water in combination with planned environmental water allocated through shared water plans aims to reinstate a more natural wet–dry cycle for the lower Lachlan River and its wetland ecosystems.

Hundreds of cormorants, darter and royal spoonbills nested in Moon Moon Swamp and Australian pelicans and black swans successfully fledged at Lake Brewster.

The nationally vulnerable southern bell frog was confirmed in 2 locations of the Great Cumbung Swamp area, and the nationally endangered Australasian bittern was heard in one location. Southern bell frogs were last recorded in the lower Lachlan in the 2012 floods, and there have been few records of Australasian bitterns in the Great Cumbung in recent decades.

CEWH-funded monitoring confirmed evidence of golden perch spawning and recruitment, with larval fish and juveniles observed for the first time in 7 years of monitoring. Natural cues such as temperature and rising water levels seemed to favour spawning, with recruitment supported by the extended inundation of in-channel and off-river habitats.

Aerial view of Blimebung Swamp, part of the Great Cumbung Swamp, after inundation