The 2018–19 water year was hot and dry with limited rainfall and low natural flows.

The Barwon–Darling watercourse relies on rainfall and inflows in its tributaries to support river health downstream. Some of the tributaries which flow into the Barwon–Darling watercourse are regulated by dams and weirs, while others are not. This influences the ability of water managers to actively plan events to enhance river and wetland outcomes.

In 2018–19, the Barwon–Darling watercourse experienced:

- less variability in flows

- an increase in the duration of cease-to-flow periods

- fewer and smaller pulses

- an overall reduction in the amount of water reaching the Lower Darling.

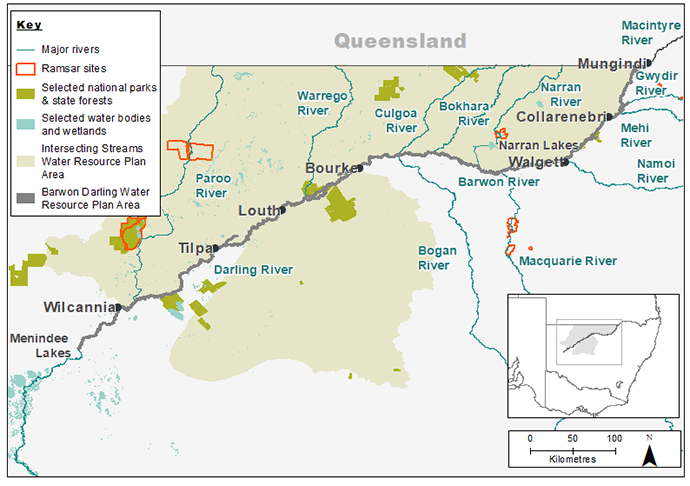

Map of the Barwon-Darling and Intersecting Streams catchments showing waterways, wetlands and locations of water for the environment deliveries made in 2018–19.

Watering aims

By the end of summer the Barwon River had dried back to a series of isolated waterholes which risked the survival of native fish. In response, the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder and the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment – Environment, Energy and Science (DPIE–EES) Water for the Environment Team combined resources to top-up waterholes along the Dumaresq, Macintyre, Gwydir, Mehi and Barwon rivers.

It was expected flows in the river would:

- help keep the rivers healthy

- support important Aboriginal environmental, cultural and spiritual values

- help local river communities

- contribute to town water and basic stock and domestic water supplies

- create wellbeing and recreational benefits.

Water delivery

The Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder (CEWH) used 7.4 gigalitres from Glenlyon Dam in the Border Rivers catchment to inundate rivers downstream. We worked with the CEWH to manage 28.6 gigalitres from Copeton Dam in the Gwydir catchment to replenish pools in the Barwon River – CEWH contributed 10.6 gigalitres and we contributed 18 gigalitres.

The release of 7.4 gigalitres from Glenlyon Dam in Queensland provided a flow at the top of the Barwon River at Mungindi, with a total flow of 1.25 gigalitres over 38 days in late May into June 2019. That release replenished about 470 kilometres of river upstream of Mungindi and 125 kilometres of river downstream but did not reach Collarenebri.

The release of 28.6 gigalitres from Copeton Dam provided a flow at Collarenebri on the Barwon River totalling 15.35 gigalitres over 68 days between May and August 2019. Before the water arrived at Collarenebri, the Barwon River had ceased to flow for 177 days. Around 430 kilometres of the river between Collarenebri and Brewarrina benefited from water delivered from the Gwydir catchment.

Outcomes

The Barwon River ceased to flow for about 200 days and the amount of water provided was not expected to reach as far downstream as the Northern Connectivity Event in 2017–18, which reached Wilcannia. It was anticipated the flows would provide some benefit, from Mungindi to the Brewarrina Weir pool.

Before the delivery of water, fish in the isolated waterholes of the Barwon were showing signs of stress due to over-crowding, reduced food availability, and poor water quality. These signs included a relatively high incidence of lesions and parasites on native fish. Some fish were underweight. In March 2019, the death of about 200 fish on the Barwon River near Calmundri Weir confirmed the water quality in some pools had become very poor.

No fish kills have been reported in the system since the water delivery. It is expected the topped-up weir pools will provide a buffer as we move back into warm weather and hopefully allow fish to survive in replenished refuges until the next significant rainfall in the northern basin.

Case study

Native plants and animals are not the only ones to benefit when rivers are flowing.

The Northern Fish Flow, which was planned and delivered as a partnership between New South Wales, Queensland and Australian government agencies and the broader community, targeted rivers in the northern basin, also provided important social and cultural outcomes for communities along its path.

The flow filled the Collarenebri, Walgett and Brewarrina weir pools providing much needed relief and hope to communities who had watched their river run dry in places. As water for the environment made its way along the river, the number of people fishing, camping and generally enjoying the river increased.

Seeing the flow return was culturally significant for local Aboriginal communities, as the river is central to their dreaming and everyday life.

The event also provided a lifeline for native fish stranded in refuge pools scattered along the length of the river. It improved dissolved oxygen levels, increased availability of food and provided an opportunity for fish to move along the rivers.

Water just arriving in the Barwon River upstream of Walgett. The photo shows the distressed condition of riparian trees.