What do they look like?

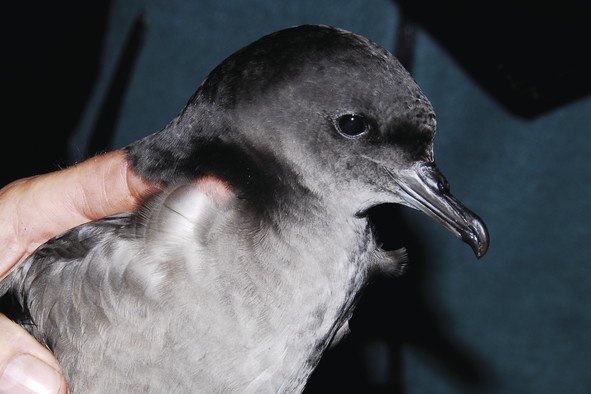

Shearwaters can be recognised by tube-like nostrils at the base of their beaks. In most species, the top of the wings, back and head are dark brown in colour. The lighter colour of the underbody varies between species.

Shearwaters earned their name by their ability to cut – or shear – the water with their wings, although until recently they were known as 'muttonbirds'. This name was given to them by early European settlers, who killed the birds for food and found that their flesh tasted like mutton.

What do they eat?

All shearwaters fish for their food. They have various fishing techniques: they can dive while in flight, or dive while swimming on the water's surface, or 'fly' underwater with half-open wings. Fish, squid, crustaceans, molluscs and plankton form the main part of their diet, but some species of shearwater follow ships for scraps or scavenge for food at offshore waste-disposal points.

Breeding

Usually shearwaters only visit land to breed. They establish colonies on remote islands, capes or coastal mountains in places where take-offs are helped by winds and there are few land predators.

Four species breed on islands off the NSW coast each year.

Flesh-footed shearwater

The flesh-footed shearwater returns from the seas off Japan and Siberia to the same nesting burrows on Lord Howe Island – this species is listed as vulnerable in New South Wales.

Sooty shearwater

The sooty shearwater returns from the North Pacific Ocean and Southern Ocean to breed in small numbers on islands south of Port Stephens.

Wedge-tailed shearwater

Wedge-tailed shearwaters return from the North Pacific to their burrows on islands off the coast of New South Wales.

Short-tailed shearwater

Short-tailed shearwaters breed on islands along the eastern and southern coastlines of Australia, from the central coast of New South Wales to Western Australia.

Breeding colonies

Shearwaters lay only a single egg in burrows and rock crevices or, less commonly, under grass, bushes or sometimes in the open. Many species spend the day feeding out at sea and only return to their nests at night. Some species, like the short-tailed shearwater, gather together in the afternoon before flying ashore at dusk.

Although shearwaters are usually quiet birds at sea, their breeding grounds become very noisy, full of strange cackling, cooing, wailing or screeching sounds. You can visit a wedge-tailed shearwater breeding colony on Muttonbird Island

The hazards of migration

Shearwaters travel far and wide to places such as Antarctica, Siberia, Japan, South America and New Zealand. This often puts their lives in danger. After gales or during food shortages, dead birds are often found along the coast. In some years, enormous numbers of short-tailed shearwaters can be found dying or dead on the beaches along the coast of New South Wales.

The reasons for these deaths are not entirely clear, but scientists think that starvation and exhaustion on the birds' southerly migrations are the main causes. Adults migrate south to their breeding islands during October and, although they stock up on their food supply in the northern hemisphere, they do not find a lot to eat on their way south. Forced to fly into strong winds, the weaker birds are unable to reach their breeding grounds in Australia. They end up as casualties along our coast. This is natural selection at work. It ensures that only the strongest birds survive to breed.

Non-breeding and immature shearwaters migrate south some months after the breeding adults.

Why are there groups of dead or dying birds on the beach?

Each year, many short-tailed shearwaters (also called ‘muttonbirds’) die at sea during their migration along the NSW coast. This event is an unfortunate but natural occurrence. Every few years, wind and tides cause these birds to wash up on our beaches dead or in advanced stages of decline. Unfortunately, very little can be done for these birds, as history has shown attempts at rehabilitation by even the most experienced wildlife carers are almost invariably futile.

What to do if you find a group of shearwaters on the beach

Residents are advised to leave the birds on the beach. The natural cycle of our beaches will ensure that the birds will not remain on the beaches for an extended period of time.

Protection of native animals

All native birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals, but not including dingoes, are protected in New South Wales by the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016