What is the Barmah Choke?

'The Narrows' is found in the Barmah-Millewa Forest, north of Echuca-Moama. The Aboriginal name for The Narrows is Dunggula.

This 'narrowing' occurs at 3 main locations within the Barmah-Millewa Forest. Two of the 3 narrow sections occur along the Murray River, upstream from Picnic Point (called the Tocumwal Choke) and downstream from Picnic Point (the Barmah Choke), while the third occurs on the Edward River (an anabranch of the Murray) immediately downstream from the inlet from the Murray River.

These natural constrictions allow flows from the rivers to spill out onto the Barmah-Millewa Forest floodplain.

Together 'The Narrows' provide a unique challenge for river operators who must consider channel capacity alongside a range of other factors when managing water in the system for downstream uses.

Moira Lake, part of Millewa forest, Murray Valley Regional Park

How does the system work?

Before the river system was regulated by dams and weirs, this section of the Murray regularly spilled onto the floodplain in response to tributary inflows.

These 'overbank' flows provided seasonal inundation for adjoining river red gum forests, filled wetlands, recharged underground aquifers and reconnected the braided network of ephemeral creeks and flood runners branching out across the floodplain.

Low-level flows over summer and autumn under natural conditions gave the riverbanks time to drain, dry, revegetate and stabilise between seasonal high flows.

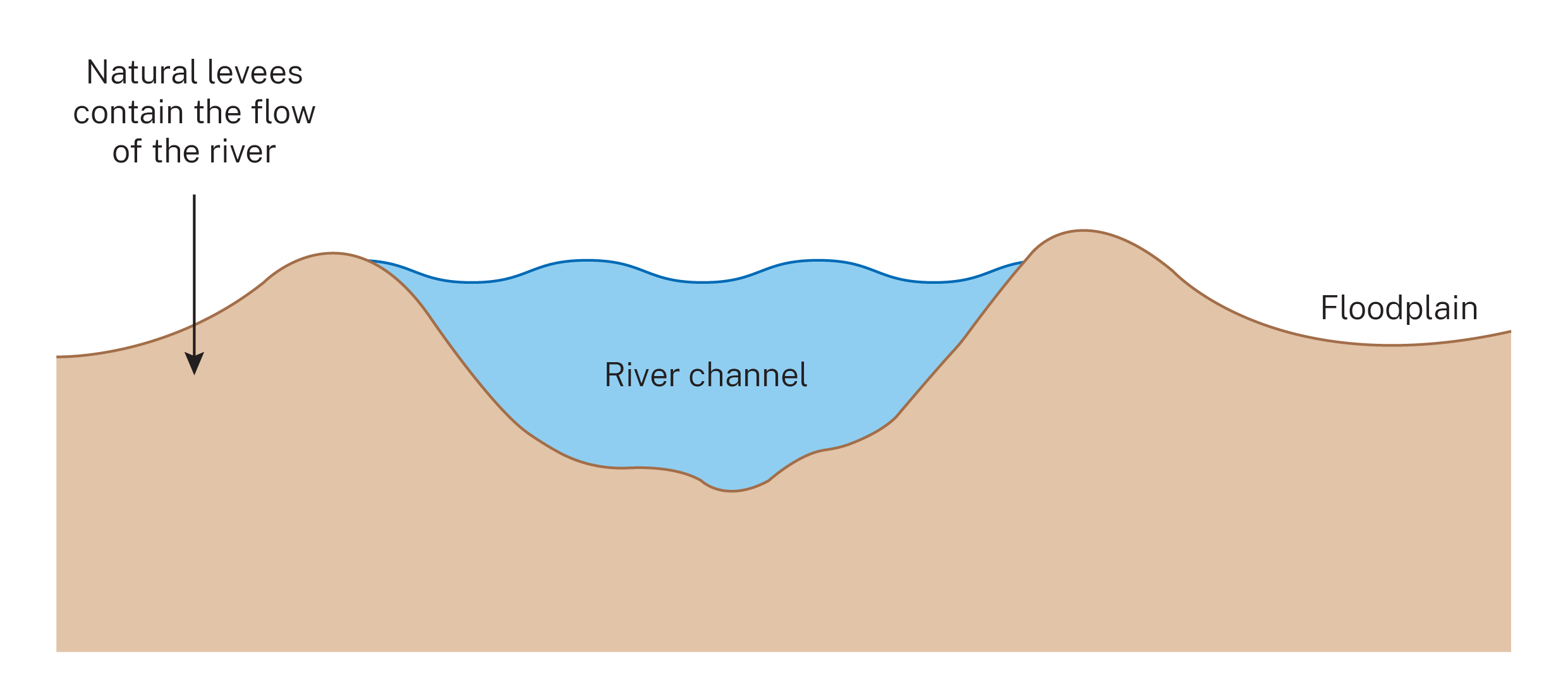

As a 'perched river', the summer-autumn drying cycle was (and is) particularly important to maintain the structural integrity of the riverbanks and the capacity of the narrow river channel.

Barmah Choke river channel. Note: The floodplain is lower than the height of the river.

Changes over time

After the installation of dams and weirs, Barmah-Millewa Forest managers and communities began to notice a decline in the health of the river red gum forests.

Due to the regulation of Murray the River from the mid-1930s, extended periods of bank-full flow over summer and autumn permanently inundated low-lying areas of forest. As a result, large stands of river red gum forest died. From the 1940s, a series of earthen banks and regulators (gated weirs) were constructed along the banks of the Murray and Edward rivers to limit unseasonal flooding of the forests.

Today, the forest regulators are systematically opened annually over winter and spring to emulate the natural flooding regime of the forest and attempt to protect the integrity of the riverbanks along the naturally 'perched' sections of the Murray and Edward rivers. These perched riverbanks or 'natural levees' are an amazing example of natural engineering processes that (prior to river regulation) were critical in maintaining the forest's natural flooding and drying cycles. Incredibly, they rarely submerge, even during major floods.

The combination of river regulation from the 1930s and the deposition of a large volume of sand due to past gold mining, land clearing and de-snagging practices has contributed to the acceleration of riverbank erosion in the reach. In many locations, the riverbanks have eroded several metres and retreated past the crest of the natural levee. In addition to this, large volumes of fine sediments have been deposited into the Barmah and Millewa forests and important open-water wetland habitats like the Moira Lake are filling with silt. Degradation of the riverbanks continues to have significant adverse impacts to Aboriginal sites and is a major threat to the Barmah and Millewa Ramsar wetlands.

How did 'The Narrows' form?

More than 65,000 years ago, a major geological event began to occur, lifting the land between Deniliquin and Echuca to form what is now known as the Cadell Fault. The Bangerang name for the Fault is Dunggudja nanit (pronounced dung-good-jah nah-nit) which translates to the great earthquake.

The fault line (measuring up to 15 metres high in parts and around 80 kilometres long) disrupted the original course of the Murray River. The river pooled and spread, forming an inland delta before forging a new path north and south.

A dreaming story describes how, several thousand years ago, Aboriginal people assisted the passage of flow from Dunggula (the traditional name for the Murray River) with their digging sticks through a low point in a sand lunette near present-day Barmah township. This allowed Dunggula to connect with Kaiela (the ancestral Goulburn River), now the present-day Murray River that flows between Echuca and Moama.

The river red gum forests we now know began to form during this period. With regular inundation from the river, the forest and floodplain wetlands evolved to support the unique array of Australian wildlife that rely on them to this day.

How does the Barmah Choke influence the environment?

Due to the constrictive nature of the Barmah Choke, when water levels rise, water flows out onto the floodplain through a braided network of anabranch creeks, filling wetlands, restoring groundwater aquifers and reinvigorating the river red gum forests and black box woodlands that have evolved in this area over thousands of years.

These wetlands, creeks and rivers provide critical habitat for wildlife, including native fish that move between the river and floodplain wetlands to feed, breed and grow. Wetlands provide a nursery habitat for native fish and ideal nesting and foraging habitat for a diverse array of waterbirds.

The Barmah-Millewa Forest requires regular inundation to return to health and remain viable. Within the forest are several important habitat sites. On the NSW side of the border, these sites include:

- Moira Lake and the surrounding Moira grass plains are known for their traditional values, with large numbers of Aboriginal sites (such as burials, scarred trees and oven mounds) located nearby. The 500 hectare lake was once a prominent native fish nursery that is becoming increasingly shallower due to it filling with silt from the Murray River. Moira Lake is an important breeding site for the nationally threatened Australasian bittern.

- Algebonia plain is highly valued by the local Traditional owner groups for spiritual reasons. Algebonia is almost lost to river red gum encroachment due to altered flooding regimes from river regulation.

- Gulpa Creek wetlands are key breeding sites for the nationally threatened Australasian bittern.

- Together, Barmah-Millewa are home to Australia's largest river red gum forest. Barmah and Millewa are both Ramsar-listed wetlands providing habitats for a diversity of wetland and terrestrial fauna, including nationally threatened species such as superb parrots, squirrel gliders, barking owls, and migratory bird species that are listed on bilateral migratory bird agreements between Australia, and Japan, China, and the Republic of Korea).

- Toupna Creek (managed as a breeding and drought refuge site for a diversity of native fish species). Large numbers of oven mounds and middens line the Toupna Creek, which indicates the creek was an important food resource for the local Aboriginal people.

- Toupna Creek flows into Douglas' wetland, which is a breeding site for the Australasian bittern. Overflows from Douglas' enter the Wild Dog Creek (named so because it 'runs everywhere'), which terminates into the Edward River.

- Saint Helena wetland (known for colonial nesting waterbirds and a range of other waterfowl, including large flocks (or mobs) of duck that are hunted by the resident peregrine falcons).

- The Bullatale, Native Dog and Tuppal creeks play an essential role in protecting the natural levees along the Murray River (the Tocumwal and Barmah chokes). Large volume of water are diverted into these creeks from the Murray River when river flows exceed 30,000 megalitres per day for the Bullatale Creek and 50,000 megalitres per day for the Native Dog and Tuppal creeks. This maintains the river water level at Picnic Point at bank full level when these larger flows arrive. This is a remarkable part of the Murray River system that is incredibly sensitive to change.

How does the Barmah Choke influence the management of water?

River operators must consider the flow capacity of the Barmah Choke when managing deliveries of water to downstream users. They take into account:

- dam releases for river operations, town water supplies, irrigation orders and river health needs

- inflows from tributaries along the course of the river, which contribute to the flow

- catchment conditions before the flow

- weather forecasts and longer-term outlooks

- travel time from the storages to demands downstream.

If flows go above 9,000 megalitres per day, Barmah-Millewa Forest regulators must be opened to protect the structural integrity of the perched riverbanks and mitigate flooding of private land around Picnic Point. While the floodplain ecosystem relies on regular watering, the timing of these flows during periods of peak irrigation demand is often out of season for the forest's needs.

Before river regulation, the Barmah-Millewa Forest flooded annually. The ecosystem evolved in response to this natural winter-spring wetting and summer-autumn drying cycle.

What are the issues relating to the Barmah Choke?

Channel capacity through the 'choke' limits the delivery of irrigation water during peak demand periods which usually peaks in summer when farmers require more water for their crops. 'Below Choke' demand seems to be constantly increasing due to expanding irrigation developments in the Lower Murray and less water entering the Murray River from the Murrumbidgee and Lower Darling Baaka rivers. Whenever the Menindee Lake Storages are empty, then additional water is needed to fill Lake Victoria from the upper Murray River storages (that is, Hume and Dartmouth), and/or the Goulburn and Murrumbidgee river storages. This places added pressure on all of these river systems.

'Rainfall rejection' is another issue that river operators and forest managers must contend with. This issue arises whenever irrigation orders are cancelled due to summer rainfall occurring over irrigated farmland, but the water has already been delivered from Hume Dam. This produces higher flows in the Murray River downstream from Yarrawonga Weir because of a sudden reduction in demand for water from irrigators. Rainfall rejection can also result in less water being diverted into Mulwala Canal and Yarrawonga Main Canal, adding to the Murray River's downstream flow. Rainfall rejection has produced unseasonal forest flooding in Barmah-Millewa in the past, especially when increased inflows from the unregulated Victorian tributaries (that is, the Kiewa, Ovens and King rivers) occur at the same time.

What are some of the actions being proposed to address the Barmah Choke?

The Barmah Choke is a naturally occurring hydrological feature integral to the functionality, health and long-term survival of forests and wetlands in the central Murray region.

Drought, climate change, river regulation, increased irrigation developments, de-snagging and introduced flow constraints are all contributing to a decline in the ecological and hydrological function of the Murray River and Barmah and Millewa Ramsar sites, and deterioration of the perched riverbanks.

Efforts to overcome the limitations of the Barmah Choke also come with potential impacts.

In recent years, a range of options has been proposed to address the issue of the Barmah Choke. These include building a channel or pipe to bypass the choke, directing flows through irrigation infrastructure and/or anabranches to bypass the choke, allowing water to overbank and flow through the forest to reach downstream users and dredging the river to increase channel capacity.

Each of these options comes with risks to the ongoing survival of our iconic river red gum forests, Ramsar-listed wetlands and unique biodiversity.

Interrupting natural flow patterns, reducing water availability and changing the geomorphology of waterways can have devastating consequences for native wildlife, vegetation and hydrological function.

In an already stressed system, further change could result in:

- unseasonal inundation leading to stressed river red gum forests

- changes to habitat structure limiting breeding and feeding habitat for aquatic animals

- reduction in the availability of water, reducing overall area of inundation and health of habitat for all species

- reduction in flow variability impacting native fish

- increase in riverbank erosion resulting in 'breakouts' and loss of vegetation

inadvertently redirecting the course of the river.

Sensitive and responsive river management is the best available tool to ensure 'The Narrows' and the Barmah-Millewa Forest flow through can be retained in good health, while also servicing the needs of downstream water users.